|

La toma de muestras en

ecopsias

Prof. Dra. Juliana Fariña*, Dra.

Concepción Millana**, Dr. Antonio de

Antonio***

* Catedrático, Jefe

de Servicio del Servicio de Anatomía Patológica II. Hospital Clínico

de San Carlos. Universidad Complutense. IMSALUD. Madrid.

SPAIN

** Profesor Asociado en Patología Molecular. Facultad de

Medicina. Universidad Complutense. Médico Experta en ecografía y

Patología Molecular. Servicio de Anatomía Patológica. Hospital

Clínico San Carlos. Universidad Complutense. IMSALUD. Madrid.

SPAIN

*** Neurocirujano, Teniente Coronel Medico. Dirección de

Sanidad del Ejército del Aire SPAIN

Key words: Ecopsia, autopsia ultrasonográfica, echospy, ultrasonographic autopsy, ecopsy, ecoopsy, ecoopsia.

|

|

Introduction

Echopsy can be defined as the pathologic study of samples obtained with the aid of ultrasonographic imaging visualization of internal organs. It is considered a minimally invasive autopsy. It was invented in 1992 and, since 1998 it belongs to the regular capabilities of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos, in Madrid. The method has been proved to have a sensitivity of 83% and a specifity rate of 100%.

After Echopsy, the external appearance of the body is unchanged; Echopsy is less time consuming that classical autopsy and it is better accepted by the family of the patient.

We intend to produce a simplified summary of our method so that it can be easily repeated by colleagues from the web.

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

|

|

B.-

Echopsy samples

We will consider three kinds of samples: solid samples, liquid samples and microbiological culture samples.

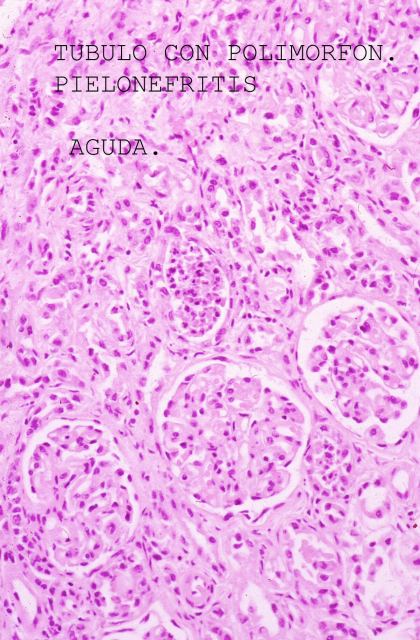

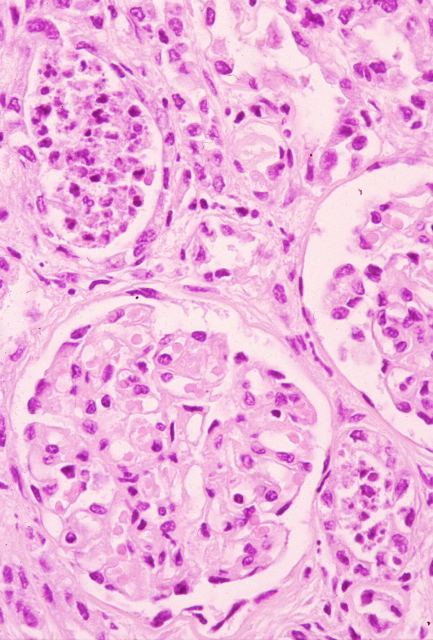

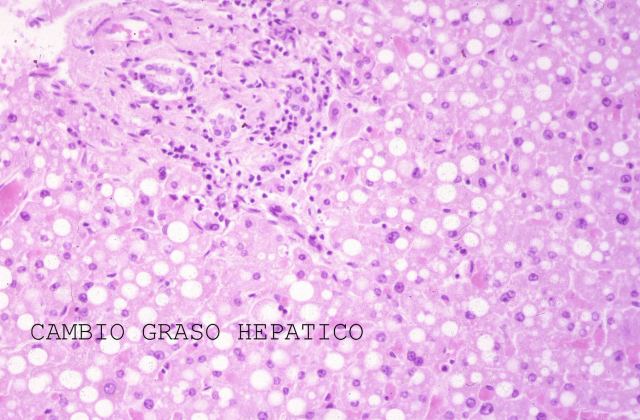

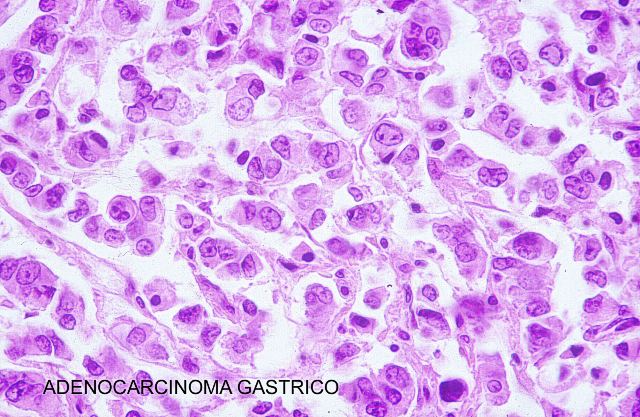

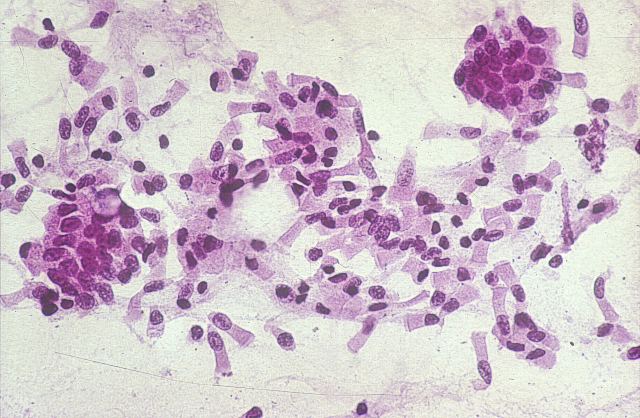

Solid samples are generally tissue fragments. Solid samples are fixed, included, cut and stained for microscopical diagnosis ( Fig.1-3).

Fig 1 shows a brain slice at low power magnification, fig 2 represents brain ultrasonography of an adult male where two metastases from lung carcinoma are shown. Microscopic study of the same sample is also shown ( figure

3).

Liquid samples are processed for cytology diagnosis.

( Fig.4 shows a chronic pleural effusion)

, and those taken for culture, are the object of a special procedure. Sample collection always follows organ, tissue or fluid collection visualization on the ultrasonographic screen

( Fig.5). Thus we can check if it has a size and shape in the normal range, and if the location is correct.

We will, at this time, observe the occurrence of unusually dark or even black areas, or clear, bright areas, replacing regular morphology. We will note the presence of cysts or nodular lesions. In general, in ultrasonography the black colour means liquid; clear, white or bright zones are air or other gas, calcium or the metal of the puncture needle. The grey shades show structures and solids organs.

B.1-

SOLID SAMPLES. NEEDLES USED:

Solid samples are the most frequent ones and echopsy diagnosis is based upon them, most of the times. They can proceed from the liver, kidney, spleen, pancreas, muscle, prostate, breast, testis, thyroid and adrenal glands, lymph nodes and blood vessels.

Solid samples need not a lengthy training to be obtained. However, some organs have particular features that should be taken into account. Thus, breast and testis must be held by hand and the pathologist or technician must be wary of an incidental puncture.

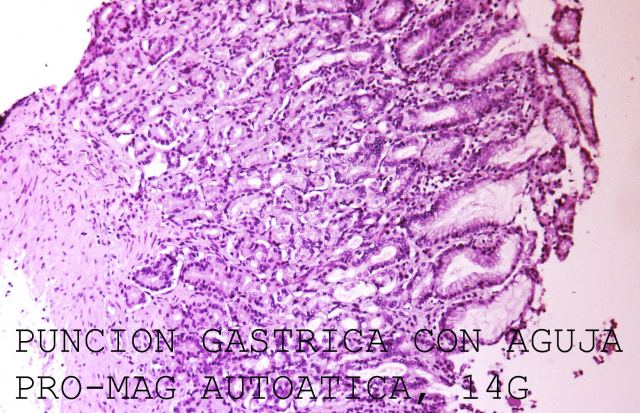

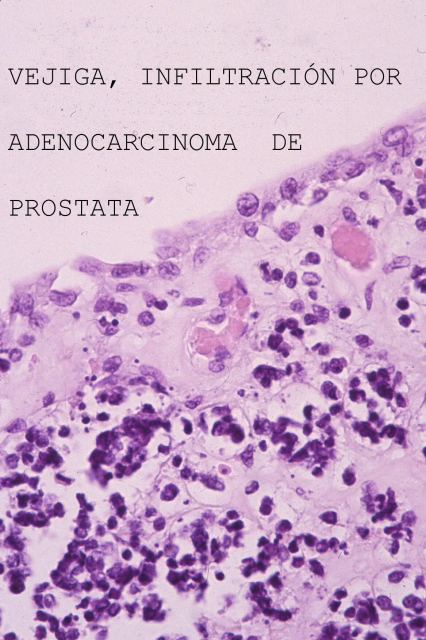

Hollow organ walls, such as digestive tract, bladder, gallbladder and blood vessels are mobile structures and it is advisable to approach them diagonally (with the needle directed diagonally) so as to stretch the tube and reduce its mobility. Fig.6 shows a sample from stomach harvested through an automatic needle 14 G bore.

Fortunately, should there be a tumour or inflammatory case, tissue infiltration reduces mobility.

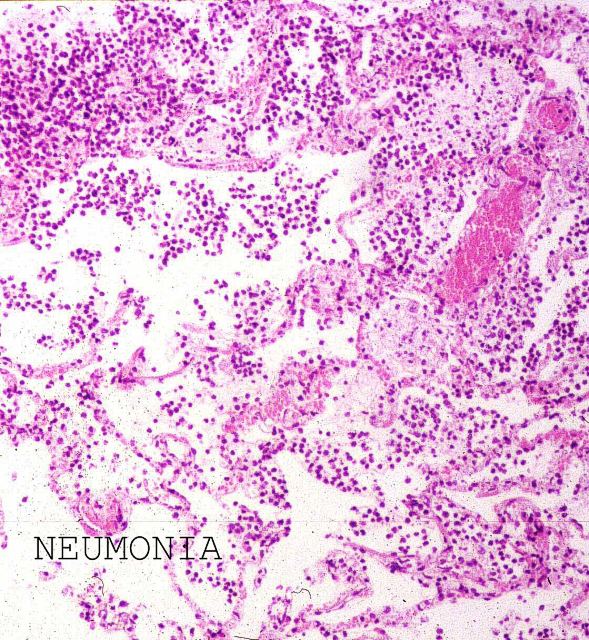

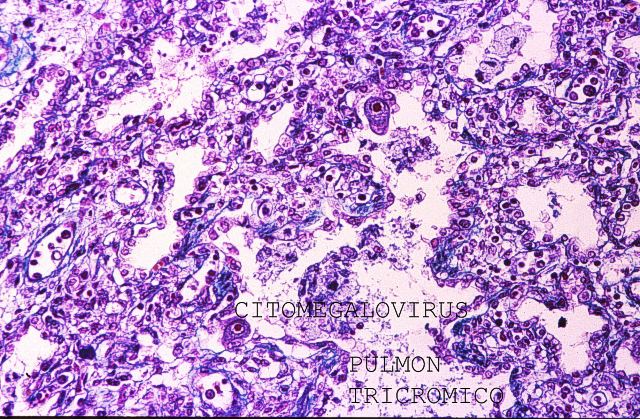

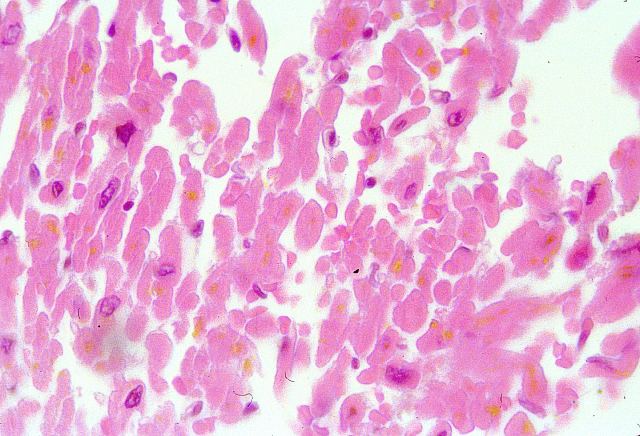

This is also the case of the lung, where normal histology frequently yields scarce material distributed in narrow strips, whereas, tumour infiltration, haemorrhage or pneumonia ( Fig.7)

, permit the collection of large, consistent cylinders in a relatively easy way. When put into formaldehyde solutions, samples tend to sink as they have been compressed and cut by the needle and will be soaked by the fixative

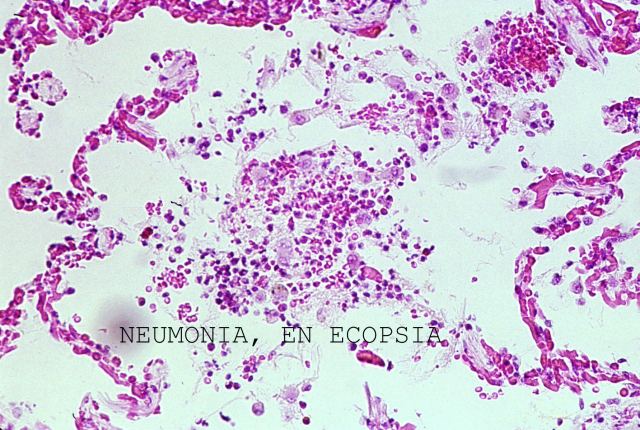

( Fig.8). This is also the explanation why pulmonary samples obtained through echopsy contain less erythrocytes, or other cells and, especially, oedema is less than the one observed in samples from classical autopsy methods. During the programming of the technique this has been shown very often and confirmed by a double blinded study (n=300) between 1994 and 1998.

Fig.8 shows an echopsy sample with scarce inflammatory cells in a case of pneumonia.

The Pancreas is easily seen in the absence of gas, so we usually start harvesting samples from this organ. Later on, the appearance of gas could prevent it from being ultrasonographically imaged.

Adrenal glands are easily seen in children and in pathological cases, when they are swollen. In normal conditions, they are difficult to spot in the adult body. Anyway, when we can perform our puncture in an area between the kidney and the spleen on the left side, and between the liver, kidney and inferior vena cava on the right. Lymph nodes are conspicuous when harbouring inflammation, tumour or haemorrhage, but they can go unseen when normal.

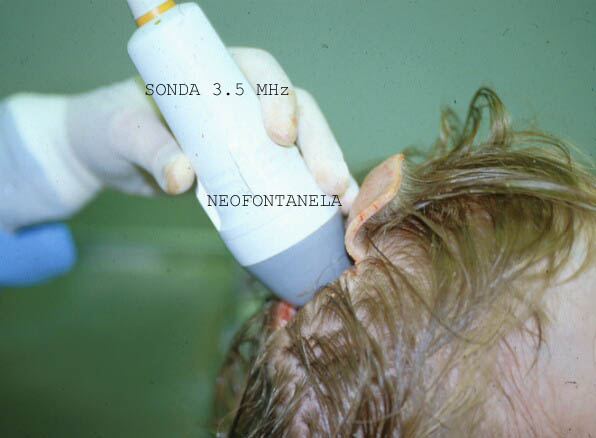

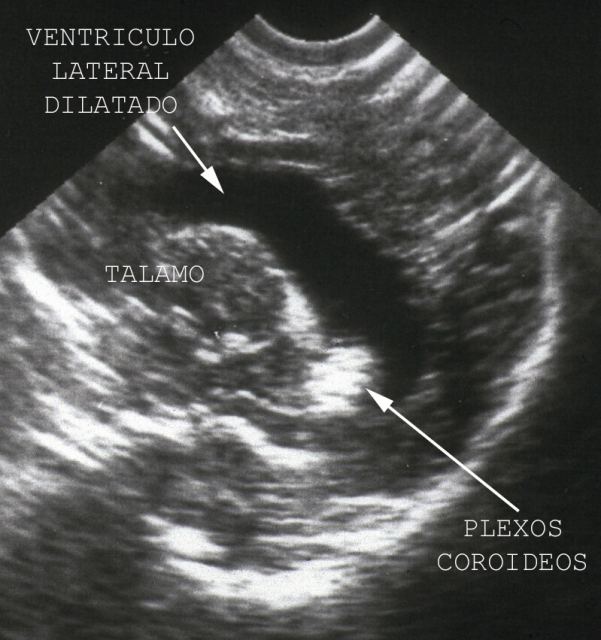

Cerebrum is studied from anatomic fotanelles in children. We make anartificial fontanelle in adults. This artificiel fontanelle is situed in the area of anterior fontanella. We perform a saw cut and a square hole some 4 cm. long. We strip the scalp, bone and dura, and we place the foot of our sound on it. From this artificial fontanelle ( Fig.9)

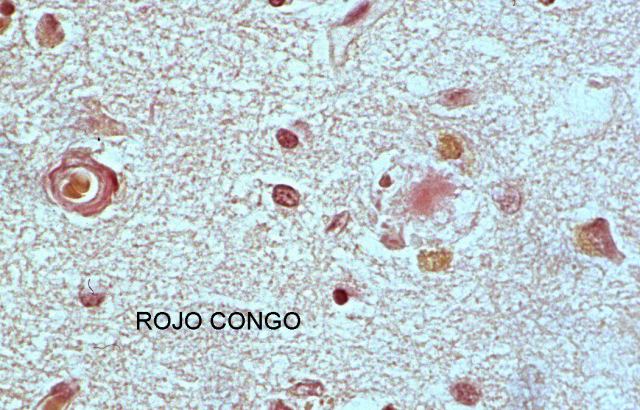

we can observe perfectly the brain and obtain samples in easy, optimal conditions. Figure

10 shows the ventricular rounding secondary to brain atrophy in a case of Alzheimer's disease. Congo Red Dye stains brain vessel walls and the plaques

( Fig.11).

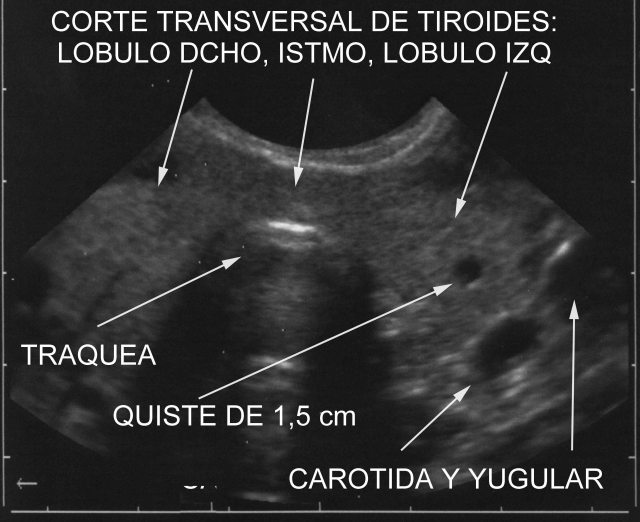

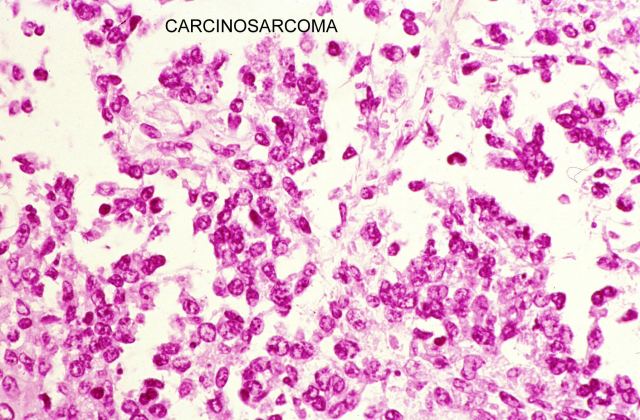

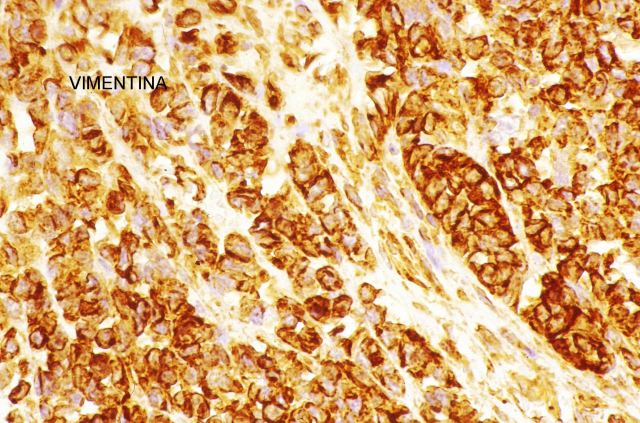

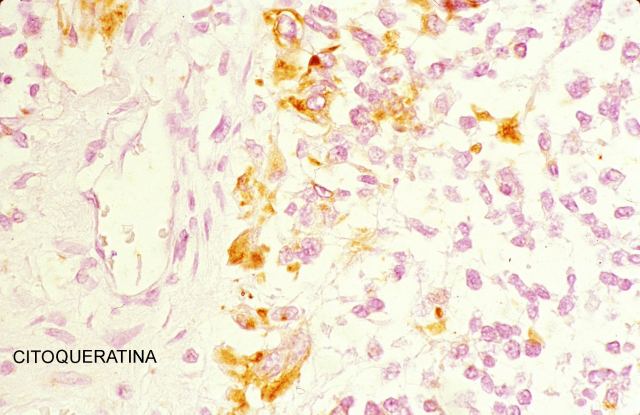

We must remember that the thyroid gland ( Fig.12), is narrow and it can be easily punctured through, the needle bore reaching the lumen of the airway, without retrieving a sample. Tissue sampling should therefore be completed with cytology aspiration with a 20 G spinal needle. Histopathological techniques, such as HE ( Fig.13-18)

, and even the more sophisticated ones

( Fig.19-20),

show better coloration, when performed on echopsy samples, than the ones obtained from classical autopsy, particularly as regards inmunehistochemical results.

( Fig.

21-22).

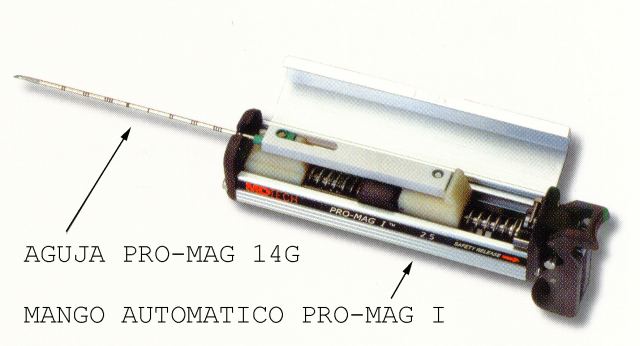

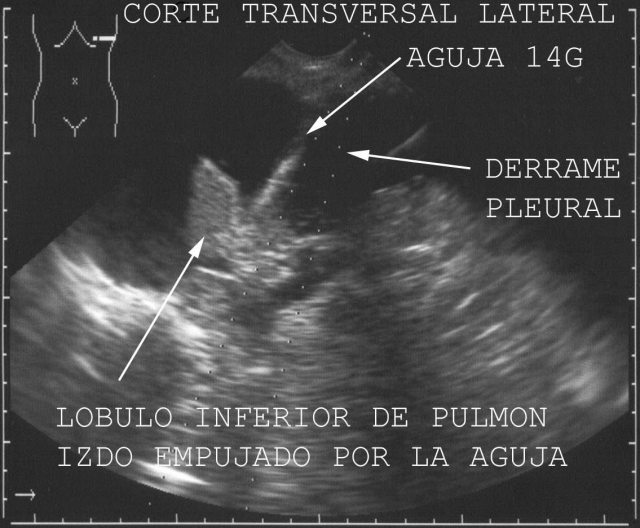

The recommend needle is ProMag ™ I 2.5 Biopsy needle ( Fig.23-25)

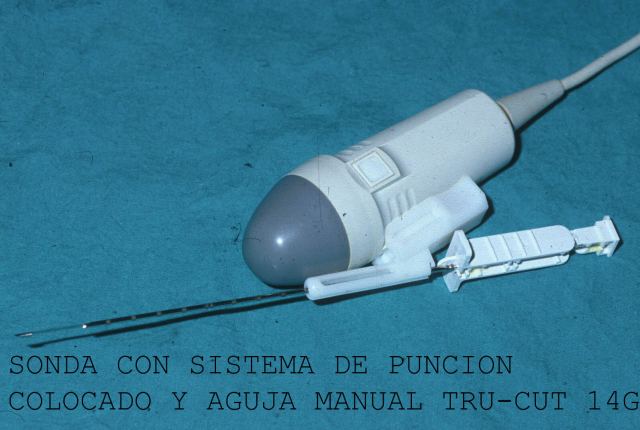

, with a 14G diameter and a lenght of 20 cm it is placed on the automatic holder PRO MAG TM I 2.5 Automatic Biopsy Instrument, which is loaded, i.e. made ready for release. Then it is inserted into the organ and released when found to be placed in the right location. This permits us to obtain the sample in an exact, automatic way, yielding a good quantity of tissue. In figure

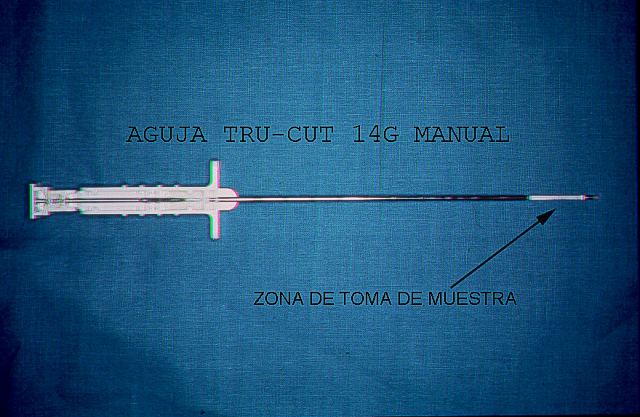

26 the needle is seen to push away the pleural membrane and the lung before actually penetrating it. Once the point is judged to be in the right location the button is pressed to shoot the mechanism and perform sample retrieval Other needles, such as the classic, hand driven Tru Cut 14G, need some training, experts can get good material for histological study and, indeed, this was the needle we have been using for several years

( Fig.27).

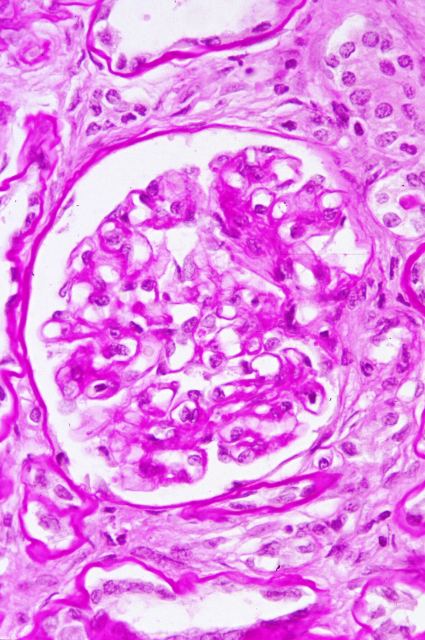

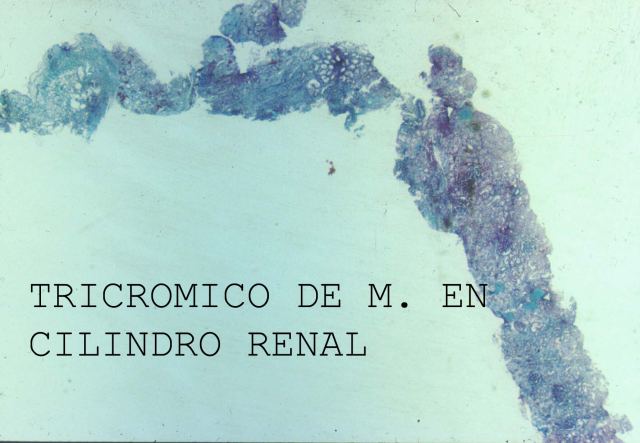

No matter the needle you use (it's easier with the automatic one), you should have a cylinder 3 to 4 cm long and 2 to 3 mm. thick ( Fig.28

shows a renal cylinder – tricromic Masson Stain).

Once the needle has been withdrawn from the cadaver, it is opened and we can visually check that there is enough material.

It is then introduced into a suitable identified plastic flask containing 10% buffered formaldehide, shaking the needle so as to release the cylinder. Now the needle is ready to be reloaded for a new puncture.

We usually employ two needles (Pro Mag or Tru Cut) for an adult. We can include the samples in capsules that are protected by a sheath of artificial sponge, immediately or after a few hours ( Fig.29)

So, Echopsy lasts as long as the biopsy procedure. As many as 4 or 5 big cylinders or multiple small pieces can be included in each block of paraffin (in case the material is fragmented ( Fig.30).

We must be reminded at this moment that striated muscle infection and necrosis of the heart tend to cause the breaking down of the tissue in small fragments that mustn't be forgotten at the moment of inclusion

( Fig.31). Big cylinders usually reflect structural normality. The opposite is true in the case of the lung.

Material can be reserved, when indicated, for inmunehistochemical techniques, nucleic acid , E/M studies, fat staining or toxicological analysis.

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

Figure 6.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Figure 15.

Figure 16.

Figure 17.

Figure 18.

Figure 19.

Figure 20.

Figure 21.

Figure 22.

Figure 23.

Figure 24.

Figure 25.

Figure 26.

Figure 27.

Figure 28.

Figure 29.

Figure 30.

Figure 31.

B.2- LIQUID SAMPLES:

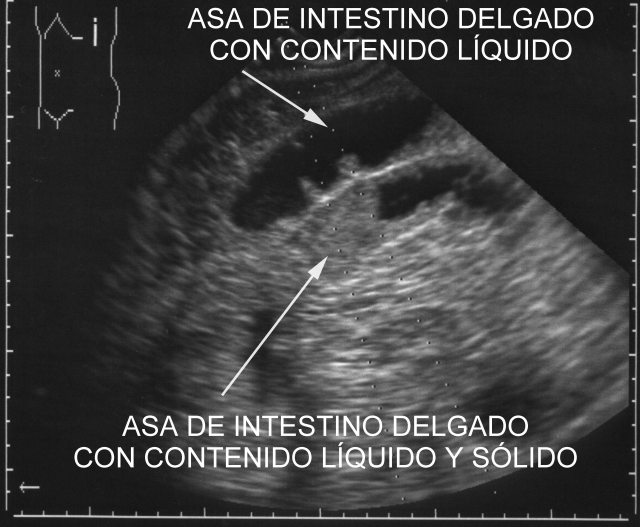

Liquid samples are drawn for anatomic cavities, cysts and hollow organs.

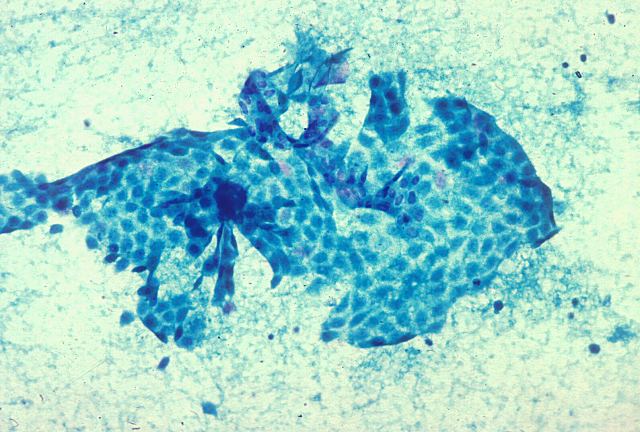

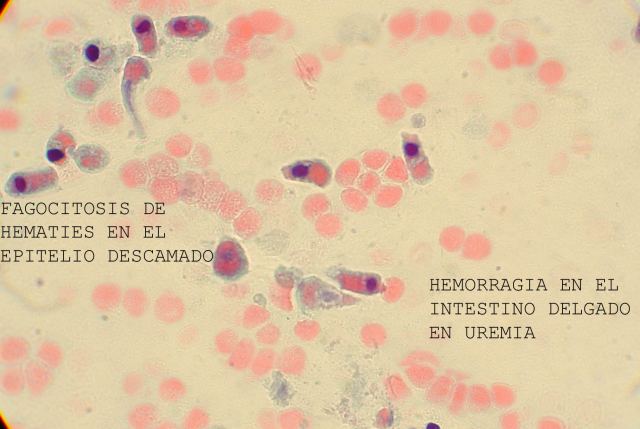

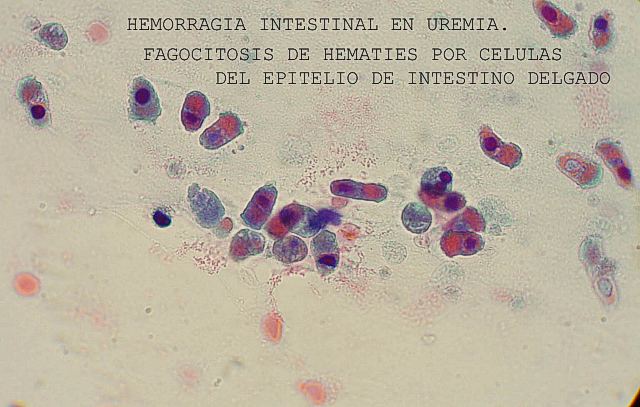

Echopsy studies have shown that cells from the innermost surface of the cavities and from the muscosal lining of the walls of the digestive troat do scarcely undergo necrosis “in situ”, but they are released and fall into the lumen few hours after death. These cells are usually well preserved and they are as useful as the ones in exfoliative cytology, faithfully informing us about the state of the mucosa “in vivo”. You can see in the figure

32 a large mesothelial cell plaque that desquamated from the pericardial cavity in a 3 year-old girl with heart failure and aspiration pneumonia. Figure

33 shows a large number of cells that have fallen into the lumen of small bowel in a young male infected with HIV.

It's of great practical importance to identify gastrointestinal haemorrhage, peritoneal haemorrhage, or pericardial or brain ventricular bleeding at the autopsy table they can be the cause of death and their diagnosis is immediate.

Further on, cytological study of the smear can inform us about other pathologies. Thus figures

34 and

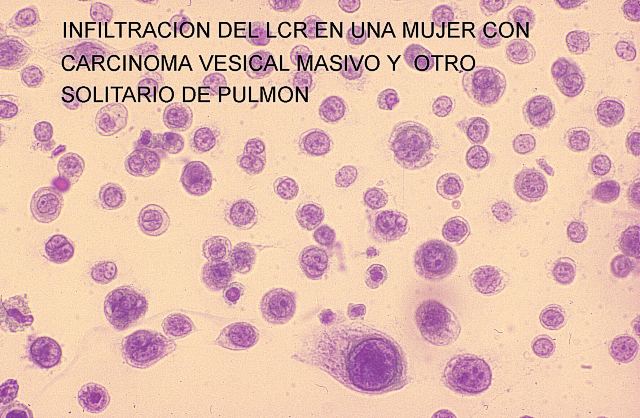

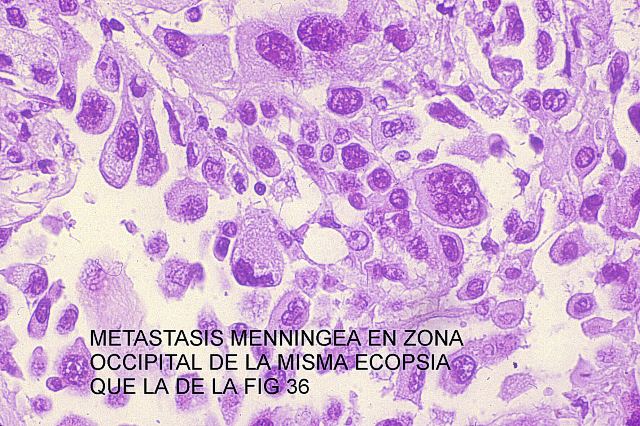

35 show phagocytosis of erythrocytes by epithelial gut lining cells that are seen to have fallen into the intestine lumen in an elderly female with chronic uraemia and GI bleeding. Figures

36 and

37 permit us to compare the aspects of a sample from a case of lung cancer metastasis and cerebro spinal fluid cytology.

Once we have located the liquid, we want to aspirate, we insert the needle and, while visualizing the needle tip on the screen of the ultrasonograph. We withdraw the mandrill and connect the syringe into the hub.

The liquid is stirred to some extent with the aid of the needle, or else we aspirate from ultrasonographically dense areas, or, if these latter cannot be identified, we aspirate from low located areas.

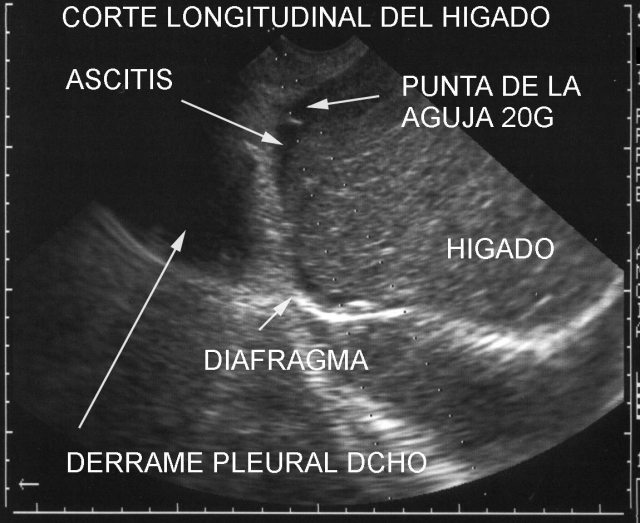

Studies have shown cytology from fluids obtained from hollow cavities with the aid of Echopsy to be more reliable and to show more pathology than those using classical autopsy techniques.

Pathological fluids (suspected to be so because of increased amount and/or density, are studied). They are aspirated through spinal needle with Quincke Type tip. We use the 20G x 90mm needle, mounted on a 20cc syringe for aspiration ( fig.

38 , fig.

39).

Should the fluid be thicker, we need a larger bore needle, such as the Surecut Menghini type 15G x 150mm (Surecut TSK modified Menghini biopsy set)

( Fig.40).

Once the area we want to aspirate is reached, we withdraw the syringe and the joined piston mandrill and replace them with a 10cc regular syringe the fluid from the syringes is immediately sent to cytology lab for processing.

B.3-

SAMPLES FOR MICROBIOLOGICAL CULTURES:

First of all, we must sterilize the area of skin where we intend to perform our puncture. It is washed and scrubbed many times with a piece of cotton. We wait for the area to dry off and then we pour Iodine Povidone on it, scrubbing with a thick cottonoid, keeping in the same direction. After a few minutes wait, we finally perform the puncture and take the sample through a surface area of 6 to 8 cm diameter. We will use a new needle for each puncture. Microbiologists need solid cylinders at least 2 cm long and liquid samples should contain no less than 8 cc ( Figure

41 and flm figure 42).

Cultures obtained through Echopsy guided punctures yield much better results than the ones obtained through classical autopsy. That is the reason why, even in those cases in which we perform a classical autopsy at our Department culture samples are always collected through ultrasonographically guided punctures.

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

Figure 32.

Figure 33.

Figure 34.

Figure 35.

Figure

36.

Figure

37.

Figure 38.

Figure

39.

Figure 40.

Figure 41.

|

|

C.-

Ultrasonographic Sounds

Adults:

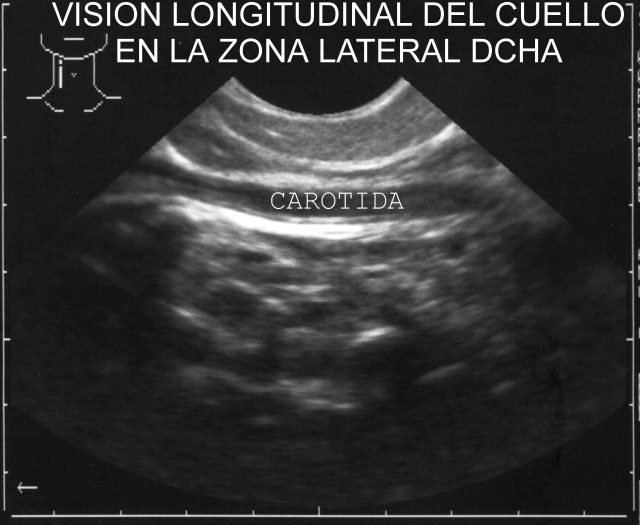

Deep organs----------------------------------------------------- 3,5 MHz sound (Fig.43).

Surface Shallow organs

Such as Thyroid, Breast, testis, |

-- 7,5 MHz sound |

Muscle abscesses, carotid arteries, jugular veins |

Eye, skin and New born, --------------------------------------- higher than 7,5 MHz

In all cases, we adapt a puncture system, with mounted needle, be it ProMag, tru Cut or an aspirating needle (Fig.44) . In this way, we locate the needle on the screen in an area between two rows of very visible dots. (Two dotted lines) (Fig.45).

All that we have to do is place the target within this area between the dotted lines and get the sample.

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

Figure 43.

Figure 44.

Figure 45.

|

|

D.-

Anatomic points and areas for sample harvesting

There are several points or areas where experience shows that echographycal visualization can be enhanced by gently manoeuvring the sound. Slices of the cadaver in different axes are represented on the screen.

In all the marked points and zones we place the ecographic sound. With it, we make longitudinal and transversal visual cuts from the corpse. The resulting cuts are shown at the screen. We can also have a wide view of nearby areas by making with our hand very gentle movements to shift the angle of the sound from a right to left and up and down. Sometimes, we move smoothly the sound in order to follow along some structures like blood vessels.

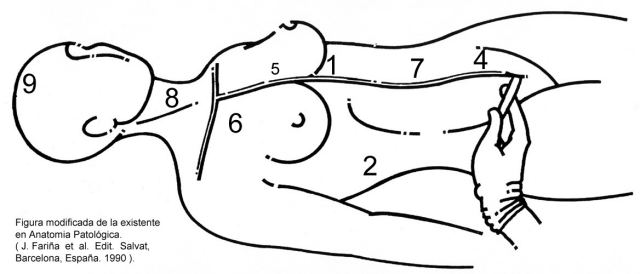

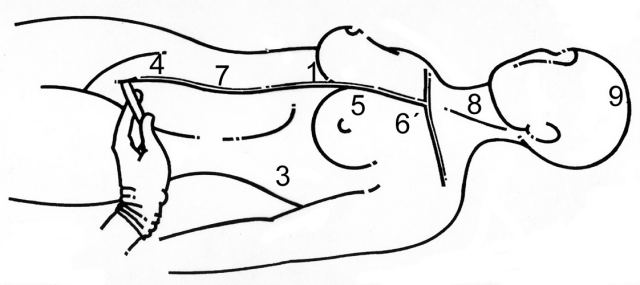

We would like to expose the points or zones that are being used more frequently and the anatomic structures currently seen. In the two schemes of the human body ( figures

54 and

55), we have marked the ecographic points, as follows.

Punto

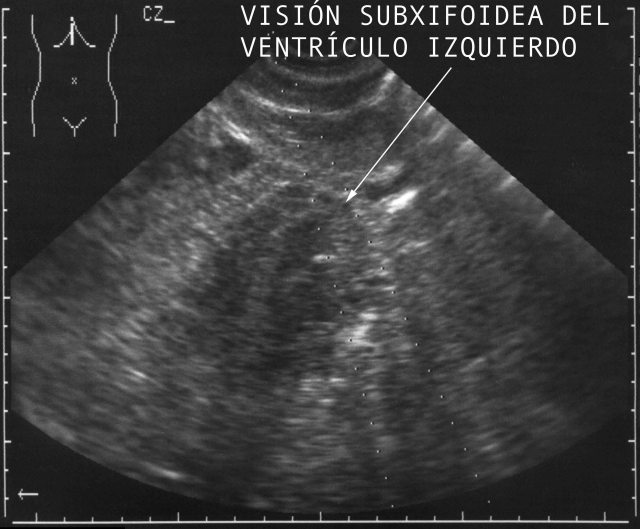

1: Subxifoid or Epigastric. You can see pleural efussions. pericardial effusions, ascitis and organs: pancreas, stomach, duodeno, heart ( fig.

46)

, liver

(fig. 47), aorta artery and inferior vena cava.

Punto

2: Includes the zone with the right costal edge. Starting at the subxifoid point to get to the axillary posterior right line and the costal edge. When there is a lot of gas in the corpse, we make a similar travel, but above the costal edge. Making with the sound the movements we have already explained, we will find liver lobes, liver vessels, gall bladder ( Fig.48),

biliary tract, right kidney and adrenal gland and right colon.

Punto

3: At the crossing of the posterior axillary vertical line and the 7 th to 8 th . Intercostal space. Spleen, left kidney and adrenal gland and left colon .

Punto

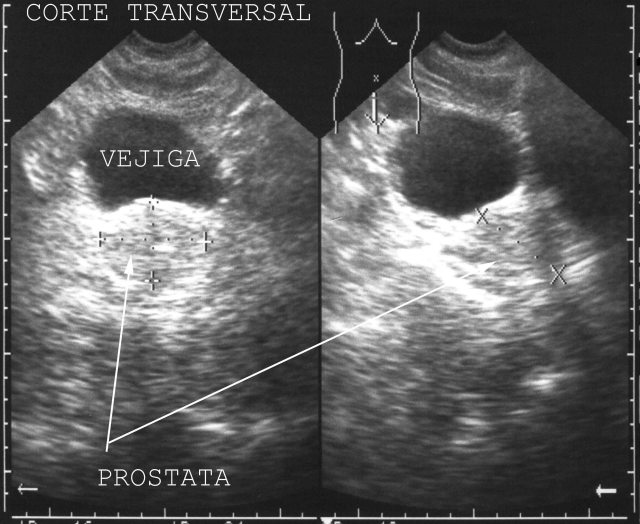

4: Suprapubic. You can see bladder (if it is full) or there is peritoneal effusion, rectum, prostate in the male ( Fig.49)

, and uterus and ovary in the female.

Punto

5:

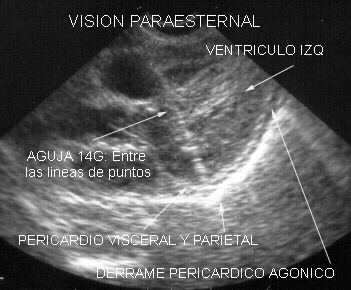

Mean left parasternal zone. Heart walls and cavities, outlet of great vessels, pericardial effusion. ( Fig.

50).

Punto

6 y 6’:

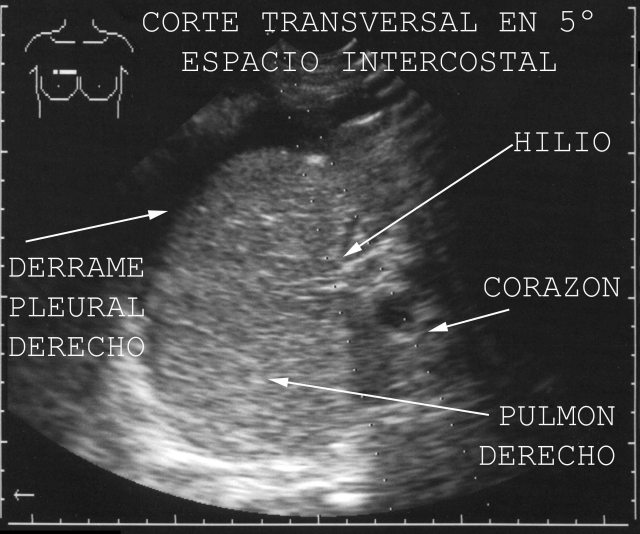

At the crossing of both sides, clavicular middle vertical lines and 2 nd to 4 th intercostal spaces of both sides, we visualize lungs and take samples from them. Figure

51 shows findings of Acute Respiratory Distress in a cadaver from the Intensive Care Unit. For the lower pulmonary lobes we aim immediately above point 3 (both sides, right and left).

Punto

7: Deep arteries and veins follow a line drawn from xifoid appendix to umbilicus.

Punto

8: anterolateral neck area Sound of 7.5 MHz. Gland thyroid, carotid arteries and jugular veins. ( Fig.12,

52 and

53).

Punto

9: Sound of 3,5 MHz. From still open fontanelles in children and from artificially made ones in adults, lines of cut and angle shifting are gently performed, so as to get suitable slices on the screen of our ultrasound equipment. We regularly compare rigut and left sides and evaluate midline shift, to identify pathology.

The corpse is laid supine and the ultrasonographic study is usually made by two persons. It has been performed by general practitioners, pathologists, radiologists and pathology technicians.

Echospy shows focal lesions bigger than 3 mm in the organs. It also shows diffuse diseases like hepatitis.

We take samples for the microscopic study the lesions, organs and in case the image is not very clear or it is hard to understand , as it is the so-called “final eye”. .

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

Figure 46.

Figure 47.

Figure 48.

Figure 49.

Figure 50.

Figure 51.

Figure 52.

Figure 53.

Figure

54.

Figure 55.

|

|

E.-

Statistics study

Statistic study by P. Pras in 130 echopsy follows the autopsy show the concordance (global Kappa index of 0.92) and validity of the criteria (sensitivity and specificity) was assessed contrasted whit autopsy. The reliability interval is 95% of the concordance for both techniques.

Echopsy· s sensitivity in bacterial pneumonia is 91.7% , 85% in acute myocardial infarction, 50% in acute colitis , 33.39% in pulmonary thromboembolism and in the remaining cases 8numbers 2,3,4,5,6, in table I) in which there was only one of each, the sensitivity was 0. The specificity was 100% in all cases.

DISCORDANCES BETWEEN ECHOPSY AND AUTOPSY IN CAUSE OF DEATH:

|

ECHOPSY |

AUTOPSY |

| 1 |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Mycotic pneumonia |

| 2 |

Acute pulmonary oedema |

Bacillus anthracis laryngitis |

| 3 |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

Intestinal infarction |

| 4 |

Anoxia |

Complex cardiac malformation |

| 5 |

Hemopericardium |

Cardiac rupture |

| 6 |

Sarcoidosis |

Pulmonary thromboemblism |

| 7 |

Lung carcinoma |

Pneumonia |

| 8 |

Cirrhosis |

Colitis |

| 9 |

Aspiration pneumonia |

Pulmonary thromboembolism |

| 10 |

Chronic hepatitis |

Acute myocardial infarction |

130 cases: 101 adults and 29 children. P. Pras in Applications of ultrasonography on the postmortemexamination (Ecopsy) in humans (sic). J.E.M.U. 1998, 19. 280-286. |

|

References

1.- Fariña J.

La autopsia ecográfica. Rev Clin Esp 1996;199: 49-51.

2.- Fariña J.

La autopsia ecográfica: Una técnica no invasiva. Sci Am (Edic

esp)1996; 241:82-83.

3.- Farina J,

Millana C, Blanco ML, Fernández MJ, Furio V, Aragoncillo P, et al

Ultrasonographic autopsy or ecoopsia:A Noninvasive Technique. Acta

Cytol 1996; 40 (4):808-809.

4.- J. Fariña.

Citopatología de la pleura en Citopatología Respiratoria y Pleural,

de J fariña y J Rodríguez Costa; Ed. Panamericana. Madrid 1996; cap

9 pag 138.

5.- Fariña J

Millana C. Applications of ultrasonography on the post-mortem

examination (ecopsy) (sic) in humans. JEMU 1998; 19:280-286

6.- Millana C,

Fariña J, Puig A. Cytopathology in Ecopsy. EJULE8 1998; 7 (suppl 1):

20.

7.- Fariña J.

Ecopsia: Técnica postmortem minimamente invasiva. An Real Acad Nc Md

1998:703-705.

8.- J Fariña, C

Millana, MJ Fdez-Aceñero et al. Rentabilidad de la ecopsia. Rev Clin

Esp 1999;199: 650-652.

9.- J Fariña, C

Millana et al. Técnica de Ecopsia para cadáveres de adultos. Cuad

Med For 1999; 18: 55-70.

10.- Chao M, Lopez A, Furio V, Ruibal J,

Millana C. Necrosis centrolobulillar hepática en un caso de

aspiración pulmonar masiva. Cuad Med For 2000;19: 37-42.

1 1.- Pacheco Cuadros R, Sendino Revuelta

A, Hernandez Albujar S. Ultrasonic autopsy or ecopsy. An Med Interna

2000 Sep; 17(9):457-9.

1 2.- JA Cobo, J Aso, M Rodriguez, C Millana, J

Fariña. Protocolo de toma de muestras en la autopsia forense

minimamente invasiva. Cuad Med For 2000; 22: 4-16.

1 3.- Roncero, J Fariña, C Millana et al.

Síndrome constitucional con impotencia funcional de miembro inferior

izquierdo en varón de 76 años. Sesión Clínica Cerrada. Rev Clin Esp

2001; 201:46-51.

1 4.- F Torres Seco. Manual de técnicas en

histología y Anatomía Patológica. Ed Ariel 2002 (Barcelona); pag

108.

1 5.- Fariña J, Millana C, Fernández-Aceñero MJ

et al. Ultrasonographic autopsy (echopsy): a new autopsy technique.

Virchows Archiv. 2002;440(6):635-9.

1 6.- J Fariña. Autopsia ecogrçafica (ecopsia)

Rev Esp Ecogr Dig 2003; 5(2):51-9.

1 7.- JM Rivera Pomar. Una apología del

diagnóstico citológico sobre material en fresco. Rev Esp Patpol

2003; 36 (1): 45-52.

1 8.- 18.C Millana. La autopsia ecográfica

(ecopsia) como exploración complementaria para el médico forense.

Plan de Formación Continuada para médicos forenses. CEJAJ (Centro de

Estudios Jurídicos de la Administración de Justicia).

2004:697-721.

1 9.- Uchigasaki S, Oesterhelweg L, Gehl A,

Sperhake JP, Püschel K, Oshida S, Nemoto N. Application of

compact ultrasound imaging device to postmortem diagnosis. Forensic

Sci Int 2003; 140: 33-2.

20.- Fariña J, Millana MC, Fernández-Aceñero

MJ. Ultrasonographyc autopsy. Histopathology. 2004 Sep;

45(3):298.

2 1.- Torrea-Gárate R, Alvarez-Rodriguez E,

Bilbao Ormazabal N, Ciguenza R, Pérez Pérez J, Millana C, Fariña J,

Lozano Tonkín C. Dolor abdominal e inestabilidad hemodinámica en

paciente con pluripatología. An Med Interna. 2004 Dec; 21(12):

615-6.

2 2.- Wright C. and Lee RFJ. Investigation

perinatal death: A review of the options when autopsy consent is

refused. Arch. Dis. Chilh. Fetal neonatal ed. 2004;

89:283-289. |

[Top] [Introduction] [Echopsy samples] [Sounds] [Anatomic Points] [Statistics] [References] [Spanish]

|

[SPANISH]

[SPANISH]

[SPANISH]

[SPANISH]